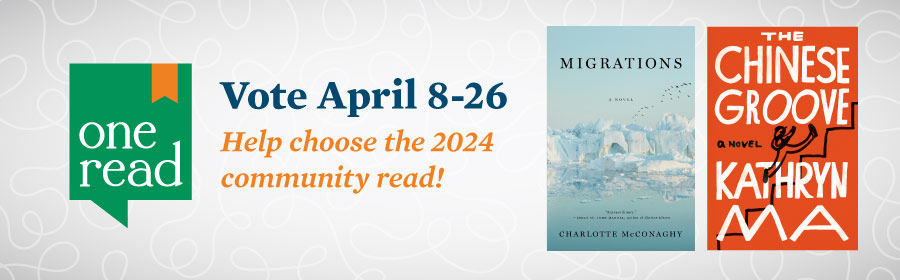

It’s time to cast your vote for the 23rd annual One Read community reading title. Our reading panel narrowed the list of community-nominated books down to two finalists: “The Chinese Groove” by Kathryn Ma and “Migrations” by Charlotte McConaghy. Both of these novels take readers on journeys far from home, full of grit, grief and the hope of redemption. You can vote April 8-26.

One Read is generously underwritten by the Friends of the Columbia Public Library and made possible by organizations in our community. We thank all of our partners on the task force for their support.